Nu Metal Pretender

It’s 2001. I’m 11 years old, a newly minted high school student. I want to learn, I want to mature, I want to experience life. Most importantly, in the short term, I want to fit in. Somehow I conclude the best way to go about this is to take a biro and draw on my forearm the nine members of Iowa nu metal band Slipknot. Let’s backtrack. As a kiddie, my musical education came through the twin strands of my dad’s record collection and the charts. I became familiar with Dylan, Oasis, the 10 or so Beatles songs he finds tolerable, and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah band via the former; your Steps, S Clubs et al via the latter.

One day at primary school, I was quizzed on my opinions concerning California pop-punk titans Blink-182. I feigned familiarity, was quickly rumbled, and set out to rectify this. Enema Of The States and, particularly, live LP The Mark, Tom, And Travis Show were enough to blow my 10 year old mind through the combination of undeniable bubblegum punk and puerile stage banter. I was instantly switched onto the joys not only of (sort of) alternative music but of discovering bands outside of the bubble of the previous generation or the will of the pop machine. Yes, I was essentially peer pressured into liking Blink-182, but that has its own purity, too.

Being a pre-ubiquitous internet age, I had to do a little digging to find new music, and in the earliest days of the new millennium, that meant leafing through magazines (to wit Kerrang!), surfing the channels, and returning to my schoolyard tormentors to figure out the next steps in my evolution. The results were two bands who enjoyed a brief but glorious time in the sun in early 2000. The first was Wheatus, whose “Teenage Dirtbag” remains a perfect soft rock nugget, but whose debut album left a lot to be desired.

More important in my development was Papa Roach. Riding the crest of the rap-metal wave, they broke big with their single “Last Resort”, perhaps one of the most successful songs to explicitly, and exclusively, address the topic of suicide. It’s lyrically clumsy (“Don’t give a fuck if I cut my arm bleeding.” anyone?), but boasts a killer riff and a staggeringly confident vocal turn from Jacoby Shaddix, who isn’t half happy with the words he’s penned. I bought the album Infest at the urging of my peers, who were convinced this was where music was heading. The train was leaving the station, and I just had to be on board.

The problem: I never quite felt comfortable with any aspect of it. The whole thing was just a bit much for me, too loud, too angry, too direct, humourless and a bit too horrid. Some of the songs like “Between Angels And Insects” followed what I’d later learn was a tried and tested quiet-loud structure; others were just loud, thrashy, studded with bits of superfluous DJing, as was the style at the time. This kind of music is meant to amp you up, or to make you feel less alone as an outcast in a world full of asshole jocks and parents who just don’t understand. Instead it made me feel a bit sad, pining for bouncy songs about girls and parties and whacking off. To admit that, though, would be to invite scorn, especially in the macho, us against them world of nu metal. Against my better judgement, I signed on for a full tour.

The big three for me were Korn, Limp Bizkit, and Slipknot. That’s about how they’d stack up in terms of importance to me. While Korn’s swampy vibe - specifically the weird little doll mascot - appealed, I could never quite buy into their brand of almost-funky metal. The singing was strange, the anger undiluted by any humour. Limp Bizkit was the more natural step for a kid infatuated with Blink-182. If Mark and Tom took their potty mouthed material close to the line, Fred Durst wasn’t afraid to stomp right over it. Their approach was somehow even less subtle than that of Papa Roach, all the anger but none of the self hatred. It’s pure performative rage; the quickly forgotten “Hot Dog” even counts the number of times Durst says the F word (46, for posterity).

The important thing for me, though, was that they had a laugh while they were doing it. They don’t give a fuck, they told us. They’d never give a fuck, unless you gave a fuck about them (and their generation - though it’s worth noting that Durst was 30 years old on the Chocolate Starfish album, making that gross title and lines like “I'm 'a keep my pants saggin' / Keep a skateboard, a spray can for the taggin'” monumentally embarrassing). The downtuned riffs on the likes of “My Generation” and “Rollin’” are boneheaded but undeniable. This is thanks in a large part to guitarist Wes Borland, whose idiosyncratic, slinky playing gives the band all of its best moments. Borland seemed prone to bouts of deep shame at being part of Limp Bizkit, leading to him repeatedly quitting the band, though he always comes back.

It’s no surprise that Limp Bizkit’s material hasn’t held up; indeed while they’re still a highly successful act in some circles, they’re a byword for the absolute worst of the early aughts in others. From the backwards Yankee cap to the macho posturing and gleeful witlessness, not to mention the spectre of Woodstock ‘99, they feel tethered to the worst aspects of an unenlightened past.

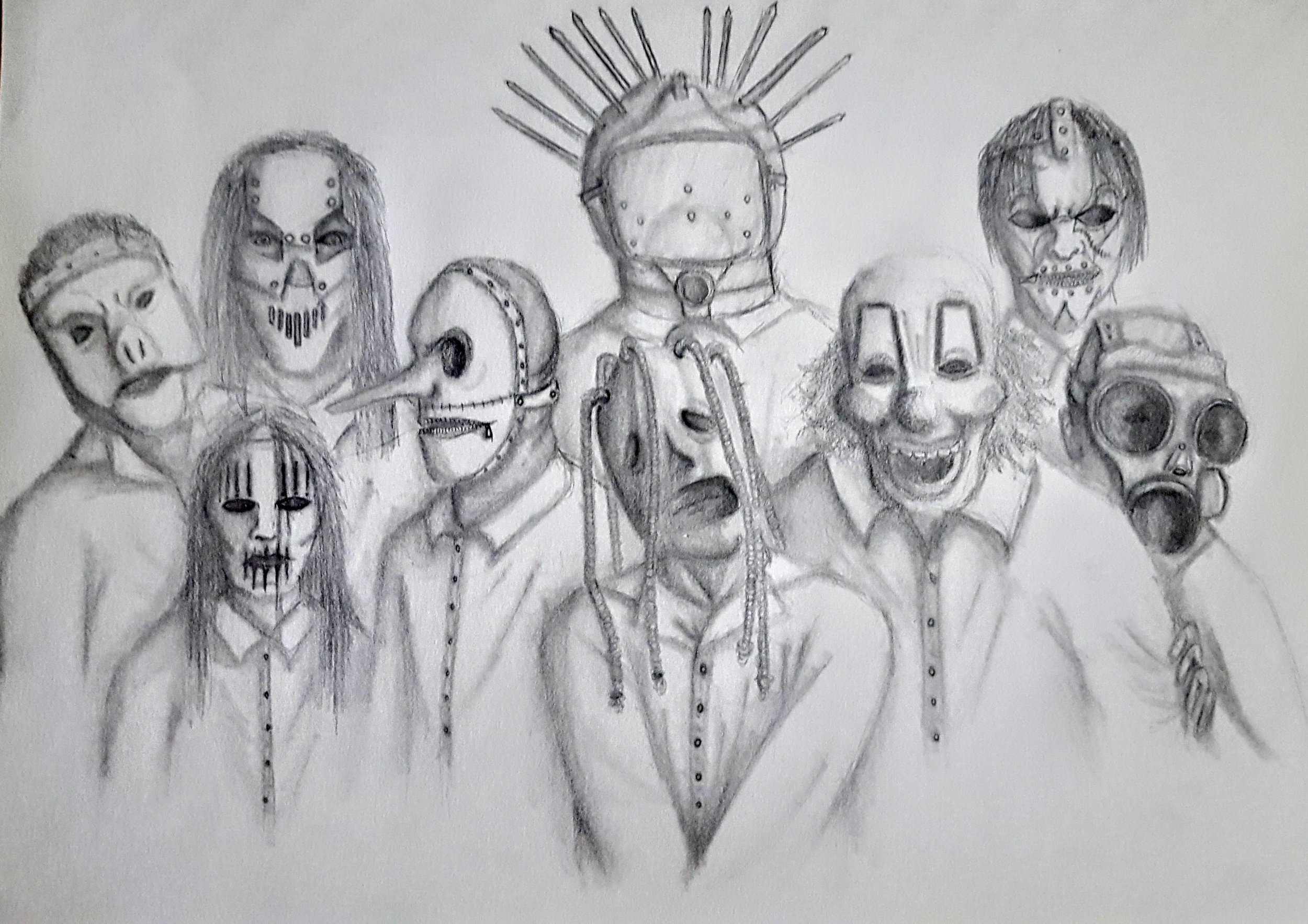

Slipknot, meanwhile, have been legitimised and elevated by the passing of time. Nowadays, they’re legends of the metal scene, festival headliners the world over, beloved by genre fans. Back in my day, they were a figure of fear and fascination. The whole aesthetic is, of course, supposed to be divisive. You see nine blokes in numbered jumpsuits and hideous masks and you’re not allowed to be ambivalent. You either think it’s gross and/or stupid and/or dangerous, or you think it’s something out of this world, the future of popular culture.

I fell into the second camp from the moment I saw them, on some old Kerrang TV compilation playing “Wait And Bleed”, one of the more accessible tunes they’d stick onto their records, presumably at the label’s behest. For an impressionable kid, it was like watching a great horror movie, only with totally alien music on top of it. Slipknot utilised the same grinding, downtuned guitars as their contemporaries, but the Iowa nonet offers an immense step up on the musicianship stakes. The late Joey Jordinson’s drumming was a technical marvel and the pummelling riffs of the hulking, genuinely frightening Mick Thompson boasted impressive variety for a genre with quite tight constraints. Vocalist Corey Taylor has some of the most discernible death growls in the game, and his guttural screams gave way to a quite nice singing voice; he’s still performing to this day, which seems a medical marvel to me.

I also liked that there were always at least two members of the band standing on stage doing not much of anything. I think the number nine has some kind of pagan significance, granting a free ride (and custom made mask) to a couple of blokes at any given time, especially when record scratches went out of fashion and their erstwhile DJ hung up his decks.

Did I like the music at the time, though? Honestly, not really. I gravitated towards the gentler songs from the first two studio albums, “Wait And Bleed” from the self-titled and “Left Behind” from follow up Iowa. They had catchy melodies, choruses you could sing rather than scream along to, but they still boasted enough danger to set you apart from the pop fans. It was a sweet spot, but it certainly wouldn’t have won me any love among the legions of Slipknot’s die hard fans, better known as “maggots”.

Not unlike the 14 year olds you see inexplicably wearing Iron Maiden t-shirts, Slipknot was primarily a lifestyle choice for me at the time. Being a fan - not listening to the music - made up a chunk of my nascent pre-teen identity. In an early year 7 art class, we were given free reign to draw whatever we wanted for a homework assignment. I drew a member of Slipknot, to wit Chris Fehn, an auxiliary percussionist who had the grossest mask in that early run: a long nosed monstrosity who looked like a peeled Pinocchio. I was given a solid 8/10 by my teacher, not a bad mark for someone with no artistic skills whatsoever. Buoyed by this, for my next assignment I drew another member of the band, this time Mick Thompson. His mask, kind of an evil welder vibe, should in theory be one of the easiest to draw, but the sharp angles and detail on the grille over the mouth proved too much for me. This time I was given a 5; I like to think the art teacher was aware of just how many members Slipknot had, and wanted to knock this on the head sharpish.

While this was the last time Slipknot and schoolwork merged, it wasn’t the last time I attempted to pay tribute to them by the medium of ink. Which brings me to sitting in class, carefully drawing each of the nine heads - from memory - onto my forearm. I was eager to prove my allegiance, using a fittingly impermanent means.

I kept on trying to really love nu metal. I wore a button up shirt with flames on it, I painted my nails black and hung around goth shops (the city of Leeds having a proud goth history, though the Sisters Of Mercy fans of yesteryear would most likely be appalled by what Corey Taylor et al were getting up to). I sewed Slipknot and Korn patches onto my school Jansport, or more accurately, I politely asked my mum to do so for me.

There has never been a better time to be a nu metal fan than the early ‘00s, when the music was mainstream enough to be accessible all over, but still carrying enough of a dangerous sheen to tick off your parents. Kerrang magazine could be obtained from your local newsagents, but I could still expect an eye roll from the old man were he to catch me with my nose buried in a copy. So if I wasn’t able to fully invest in the subgenre back then, I was never going to do so.

Ultimately what finally pulled the plug on my nu metal experiment was a band that helped to get the style off the ground in the first place - Nirvana. While there are a few steps of remove between Kurt Cobain’s groundbreaking act and the thudding wall of noise that would rise nearly a decade later, there are certainly points in common, namely angst, distortion, and a direct line to the hearts and minds of teenagers the world over.

The difference is manifest, obviously, starting from the fact that Cobain was a one in a billion musical talent and Fred Durst probably isn’t. The progressive, thoughtful, and all round decent nature of Nirvana as compared to the empty nihilism of nu metal meant there was only going to be one winner. Nirvana showed that there were ways to grapple with your confusing feelings beyond threats and middle fingers. They weren’t afraid to scream every now and again, but there were other modes of communication, too. From there I took the same journey as so many young music fans discovering Nirvana for the first time, going backwards through their influences to the Pixies, then onwards and upwards into the music I continue to listen to today.

Nu metal burned out as quickly as any substrata of heavy music I can think of, and while I by no means have my ear to the ground when it comes to that kind of stuff, it doesn’t seem to have had a particularly lasting impact. My impression is that the bands who influenced nu metal - Faith No More, Red Hot Chili Peppers - have continued to guide the way for newer acts who like to add grooves to their heavy riffs, with the bands in between little more than a blip.

In hindsight, these once-moral panic-inducing songs feel almost charmingly kitsch (with the caveat that, as a straight white man, I was hardly the target of the ire of these musicians or their fans). Specificity is everything in writing, and a threat to break “stuff” doesn’t quite pass muster. Plenty of these dumb songs have since found their way onto my running playlists and the like; as far as empty headed pump-up music goes, it doesn’t get much better.

The music doesn’t make me nostalgic in the way Blink-182 does. I don’t feel a connection to it in the way I do the music of my late teens and early twenties, when my tastes were changing and evolving and I was discovering stuff like Deerhunter and Spiritualized. Were I in a bar and a tune by Limp Bizkit or one of the handful of Korn songs I know came on, I’d rock out, sure, but I don’t think I could do so without a sense of detachment. Can you believe we really used to listen to this stuff?

That said, in recent months I have returned to Iowa, Slipknot’s second studio record. I listened to it front to back, maybe for the first time in two decades. It’s nothing short of a masterpiece, perfectly paced, colossal sounding, frightening, funny, and even catchy in parts. I didn’t see it then, but I see it now. Perhaps they’ll make a maggot out of me yet.